In 1973, Norwegian professors Johan Galtung and Mari Holmboe Ruge came up with a criteria for what deemed a story as newsworthy. The key question they asked themselves was ‘how do events become news’?

Asked how they define news, journalists sometimes reply: “I know it when I see it.”

The question of what ‘news’ is and who decides it to be newsworthy, has no straightforward answer. Information considered inconsequential to one may be vital to another, one man’s trash is another’s treasure and so on.

However, one could easily assume that the news in our newspapers every day, on our TVs every evening or our radios every morning – must have some kind of universal appeal. Much like a hotel buffet – something for everyone.

The first news sheet that we know of was circulated in Ancient Rome, the Acta Diurna, which covered important daily events and recounted public speeches. It was hung up in public areas where everyone could read it and thus the information flow known as news began. In the early stages of news there was no such thing as objectivity, fairness or codes of conduct – norms we would expect to find in any publication worth its salt today.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, news was essentially free because it was produced by amateurs for the amusement of a select few, considering the literacy rate at the time.

In November, 1670, the Dublin Gazette, which had only recently started, ceased publication because there was simply no news to put into it.

Evidently journalism, in its true sense, was not as yet understood, the first dedicated university course was not established until 1879 at the University of Missouri. As journalism developed so did the commodification of news and therefore the commercial side inevitably blended with the news side. It was no longer only the dissemination of important information to the public, it was also about turning a profit. Naturally as motives changed, the values of what shaped the definition of news did so too – and continue to do so.

In a world of 7 billion+ humans and 195 countries, considering the minutiae of 7 billion lives and everything that happens there within – it’s a valid question to wonder how news is condensed down to a relatively few stories per day. Is there a hierarchy of importance to events?

In a way there is – so called ‘news values’. In 1973, Norwegian professors Johan Galtung and Mari Holmboe Ruge came up with a criteria for what deemed a story newsworthy. The key question they asked themselves was ‘how do events become news’? Their focus was on news overseas and how it did or didn’t make its way into the Norwegian press. They looked at 1,262 press cuttings – including news items, features, editorials and readers’ letters – concerning the crises in Congo 1960, Cuba 1960 and Cyprus 1964.What they discovered was that a number of factors that seemed to be particularly important in news selection.

They condensed it down to 12 factors, among them, frequency, threshold, unambiguity and unexpectedness. Something that unfolds at a similar frequency as the news medium, like a murder as opposed to a drawn out social trend towards veganism is more newsworthy. Threshold is important too – take a particularly gruesome murder, the lurid details all help an otherwise unremarkable story pass over the so-called threshold.

Whilst the average human life is filled with complexities, it’s not necessarily something people want in their news. Multiple possible meanings will frustrate even the most loyal reader – therefore unambiguity was also cited as part of the winning recipe along with the rather expected value of ‘unexpectedness’. So far these may all seem fairly obvious values in the selection of news, but Galtang and Ruge’s list gets more specific as it goes on.

It’s hard to give a universal understanding to something so subjective as the value of ‘meaningfulness’. Often culture may play a role – what fits into someone’s frame of reference depends on various historical, social and political factors. For example, news from the USA is more likely to be seen as meaningful in Ireland than perhaps some other countries that are more difficult to relate to, particularly those in the developing world.

A basic instinct for humans is leaning towards what we already know – and so ‘continuity’ is deemed an essential ingredient. A story that has already been headline news may resurface for quite a while – once it’s familiar to an audience. Professor John Hartley makes an analogy between the news and a football game – for a player to get on the pitch ‘he must be firstly known as a bona-fide player’. Take a story that has sadly become an industry – the case of missing child Madeleine McCann. The story is raised frequently in the Irish and British press, eighteen years after her disappearance. Why this disappearance is deemed particularly newsworthy over similar cases is a prime example of several news values at once, namely: continuity, elite nations and negativity.

Whilst the press in Portugal grew tired of the case it is continuously revived by the British press upon any semblance of a clue.

Rarely do missing children get the longstanding sustained attention that the Madeline McCann case has.

Several values come into play here, perhaps chief amongst them is elitism – of nations and people. The fact that the case centered around, a young blonde child from a white middle-class background with professional parents cannot be ignored when looking at why the case appears so frequently in the media.

According to the Independent ‘some editors, it seemed, had noticed how a McCann splash could generate the kind of interest hitherto reserved for Diana, Princess of Wales’. Indeed, Madeline’s parents, Gerry and Kate McCann in a rather morbid twist of fate are now akin to an unwanted celebrity status, such was the level of press intrusion in their lives, they became key witnesses in the Leveson inquiry.

The fact that it’s a British case is also significant, what happens in elite nations is often seen as more consequential than other nations – the burning of the Notre Dame cathedral in Paris generated widespread, global coverage for an extended period. The story appeared on front pages and in news bulletins in many parts of the world – including China, Russia, Ukraine, Iran and Turkey.

One analysis found that the American media covered the Notre Dame fire (zero casualties) more than the 2020 Beirut explosion (204 deaths).

It’s worth noting that both the Madeleine McCann and Notre Dame stories were negative, the old adage that nothing spreads faster than bad news rings true, negative news stories are also generally more likely to be unexpected and to occur over a shorter period of time.

Port of Beirut Explosion, photo taken days after the explosion from an adjacent building. Photo by rashid kreiss on Unsplash

Bearing all this in mind, one wonders about the science behind news selection and how much influence an audience or readership has in determining the news they want to see/hear/read. In reference to the McCann case, Megan Nolan at the NewStatesman notes that the decision is not ours to take ‘It has been decided that this is news, and will never cease being news.’ Nolan goes on to acknowledge that

‘Newspapers are also, generally, owned and produced by a class of people with very little to lose if the status quo is maintained, and much to lose if it is lost’

Megan Nolan, NewStatesman

Noting that one does not need to be a conspiracy theorist to ‘accept that most big media organisations are profit-making businesses within a capitalist system and have the allegiances that are implied by that situation.’

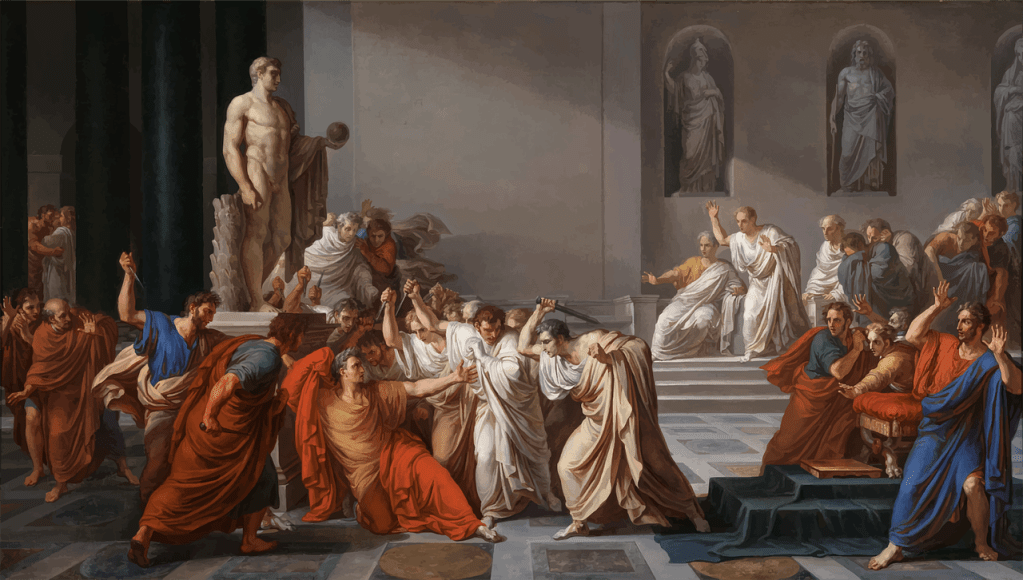

In this frame of mind, it’s plausible to question the relevance of news values or rather suppose they are just an intrinsic aspect of capitalist society. Academic commentator Jeremy Tunstall argues that these values are not news specific and indeed ‘the factors which Galtung and Ruge find as predisposing foreign events to become news – elite persons, negative events, unexpectedness-within-predictability, cultural proximity – are also to be found in Shakespeare’s plays.”

Former guardian editor, Alastair Hetherington drew up his own news values based on a study of the UK media, according to his findings journalists look for one or more of the following: significance; drama; surprise; personalities; sex, scandal and crime; numbers; and proximity. He also suggested that the real news value of any story was simply a journalist asking themselves ‘does it interest me ?’

Much like the chicken or the egg debate, it’s hard to assess which came first, the news or the journalist? Do journalists produce news or do they just report on it – or isn’t that one and the same? According to Peter Vasterman, the author of From media hype to Twitter storm, news is not just simply ‘out there’ floating around waiting to be plucked up, ‘journalists do not report news, they produce news. They construct it, they construct facts, they construct statements and they construct a context in which these facts make sense. They reconstruct ‘a’ reality.” If we think of it in this way the news doesn’t seem so credible at all, if it is selected by a relatively small number of people based on an even smaller subjective criteria.

Influential cultural theorist and sociologist Stuart Hall, took a more holistic approach by suggesting that news values act as a guide to a ‘structure’ or a ‘cultural map’ which journalists use to help them make sense of the world. This idea of the values as a guide is supported by communications theorist Denis McQuail, his book argues that the values help form a ‘predictive pattern’ of what will and will not be reported, but that the values don’t really factor in the irregularities of news composition or the influence of political and economic factors.

None of this should be taken as a conclusion that Galtung and Ruge’s study is of no value today, perhaps the values have simply changed. In 2001, Tony Harcup and Deirdre O’Neill carried out their own analysis on the British press. Forty years after the Galtung and Ruge original criteria they discovered notable differences, among them the importance of entertainment in news selection. Their analysis found that stories were often included merely to entertain, whilst noting that ‘humorous and entertaining articles, stories about sex, celebrities and Royalty – or stories which were dramatic but of no apparent widespread social significance – were not confined to the tabloids’.

Their analysis also noted that, if a story provided a good picture opportunity then it was often included even when there was little obvious newsworthiness. If the picture included an attractive female, then even better – a trend also seen on Instagram.

Mary Ann Sieghart, assistant editor of the Times, said she often heard the newsroom question: ‘Is she photogenic?’

It would therefore seem that sex sells, or atleast the suggestion of sex – the link between between this and photography of attractive females cannot be underestimated, arguably sex is a significant factor in contemporary news values. The former women’s editor of the Guardian claims: ‘News values are still male values.’ Harcup and O’Neills study does suggest that news stories frequently contain the factors identified by Galtung and Ruge, but it also shows that many items of news are not reports of events at all, with free advertising or spin making up much of it.

In a 2017 long read entitled ‘A mission for journalism in a time of crisis’ Guardian editor-in-chief Katharine Viner aptly put it as ‘We can be fun, and we must be funny, but it must always have a point, laughing with our audience, never at them. Their attention is not a commodity to be exploited and sold’.

If we can conclude anything, it’s that news values are ‘opaque’ (according to Hall) and it would seem they are.. or else conversely glaringly obvious. Perhaps the truth behind what makes something newsworthy is somewhere in the middle.

Further suggested reading:

Carter et al (1998) News, gender & power, Routledge

Galtung and Ruge (1965) The Structure of Foreign News Author(s): Source: Journal of Peace Research, Vol. 2, No. 1, pp. 64-91

Harcup & O’Neill (2017) What is News?, Journalism Studies, 18:12, 1470-1488

Hetherington, Alastair (1985) News, Newspapers and Television, Palgrave Macmillan UK

Horton, J. (1979) Stuart Hall, et al.: “Policing the Crisis: Mugging, the State, and Law and Order”. Crime and Social Justice, (12)

McQuail, Denis (1994) Mass communication theory: An introduction, SAGE Publications Ltd

Tunstall, Jeremy (1970), Media sociology : a reader / edited by Jeremy Tunstall Constable London